Getting Started and the Rule of History

Not gonna waste your time with a long intro, let's get right into it.

The Quick Intro

Hey, folks! My name is Chapin Boyer. I’m a game designer, frequent wargame player, and unfrequent (but missing it) RPG player in Brooklyn (and originally from San Francisco, a fact my friends would say they are painfully aware of).

I imagine you’ve found your way here from Luke Crane’s substack, and might be expecting more of the same. While I can guarantee my opinions are at least as strong as Luke’s, I cannot promise that I’ll be nearly as coherent or consistent. This is going to be a place for me to get my game design and writing thoughts out while I spend my days working in the code mines. If you’re down to follow along, stick around, or if you aren’t already subscribed, click this button below that they really want me to put in here.

With that out of the way, let’s jump right into our first article.

The Rule of History

In 1812, George Leopold von Reisswitz presented a new invention to the Prussian King. Reisswitz’s creation was a large table, outfitted with drawers and cabinets filled with dozens of porcelain tiles and figurines, the sum of which represented a new type of game: Kriegsspiel (literally translated as War Game) was the first, well, wargame, and it would go on to consume my life. Well, not Kriegsspiel itself – I haven’t played it (though I am desperate to) – but I have instead been consumed by its descendents. Specifically, I’m currently obsessed with Warhammer.

It’s an odd sort of hobby, Warhammer: on the one hand, it’s a game of fantastical battles in fantastical places with fantastical creatures. On the other, it is a game of deep, deep history. Warhammer and its many offshoots have been in active development since the late 1900s, and with almost half a century of lore, discussion, and games under their belts, these games are lousy with history – laden with and burdened by it.

Of course, Kriegsspiel itself was something of a “historical” game. Or perhaps it is more accurate to describe it as a simulationist game, at least when it was developed. Von Reisswitz designed the game to simulate the modern military encounters of his day, and as other officers in Germany’s fledgling military took on the task of developing the game, they continued to add new technologies. Eventually though, this development ceased. Time would stand still for Kriegsspiel, and the world’s first modern wargame became the world’s first historical wargame.

The games that would follow in Kriegsspiel’s footsteps would retain its focus on history. The Napoleonic wars that raged during Kriegsspiel’s development became (and perhaps remain) the favorite child of historical wargaming, but World War 2, the Civil War, the Revolutionary War, and even the stereotypically static World War 1 all feature myriad games set across their many, muddy, bloody battlefields. There’s a brick of these games, is what I’m saying, o it’s not so surprising that games of Warhammer would be similarly steeped in history, albeit a fictional one.

By the way, I’m using Warhammer as a catch all for basically every game made by the parent company, Games Workshop, and you don’t need to tell me that there’s a bunch of these games. I promise you I am aware, and that the rest of the audience does not care, nor does it matter for the discussion at hand.

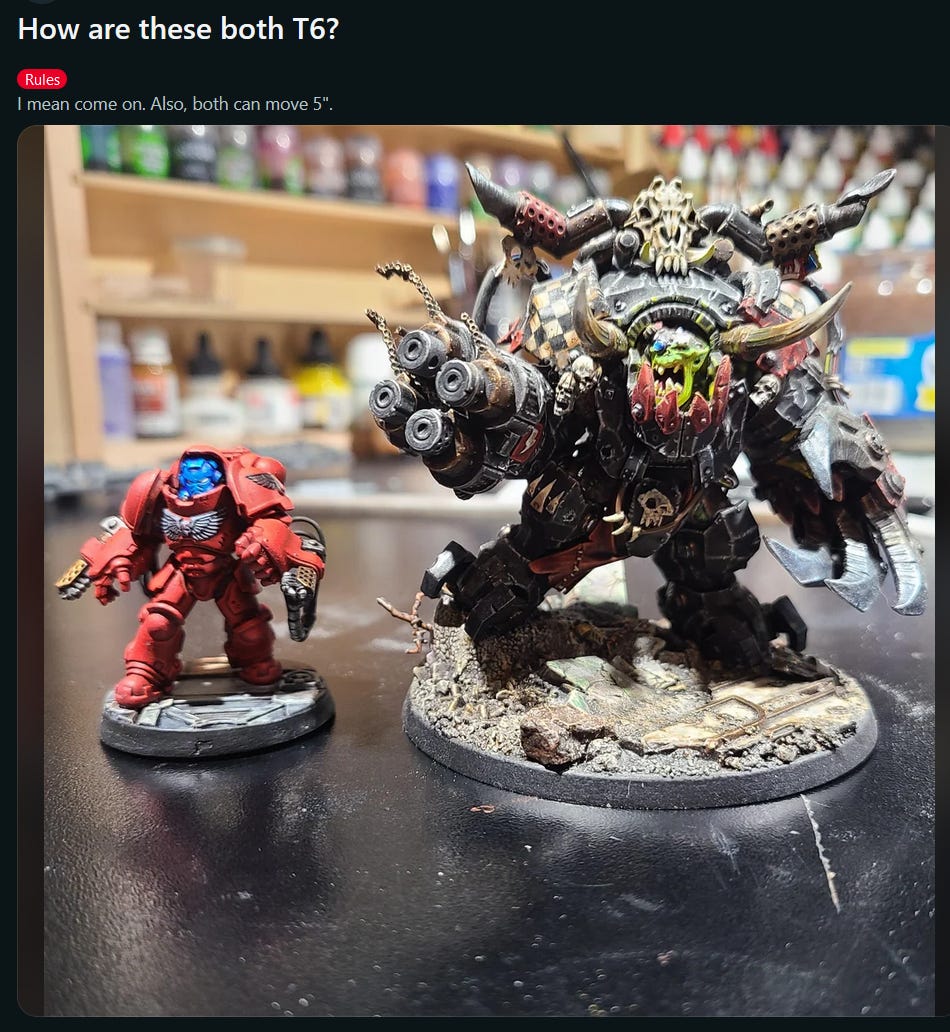

What becomes interesting to me about the historicising of Warhammer, is the way that game mechanics have become synonymous with the reality of the game world. Take this example I found on Reddit just a few days ago:

I think this might be one of the most fascinating images for the modern game designer. Ask yourself: what’s the problem here? For those not in the know T stands for Toughness, and is a representation of how difficult a target is to injure in games of Warhammer. You compare the Strength of the attack to the Toughness of the target, and that determines what you need to roll on a six sided die in order to injure the target. So what’s the issue here? No really, take a guess and see if you can get it.

Well, that space marine (the red one) is a lot smaller than Ghazghkull Mag Uruk Thraka (the big green one that originated as a parody of Margaret Thatcher), and therefore logically shouldn’t be able to take as much punishment, or at least that’s the argument the poster is making.

I want to make something clear here as well: I am at no point making fun of this person, or anyone else who operates under this kind of logic. As I’m going to show, they are not wrong to do this! And even if they were, this is a silly fun game about silly plastic men, and none of us should get too worked up about it.

So. The big green guy and the little red guy are the same toughness. If we take the argument at face value that one should be obviously tougher than the other, we have to ask ourselves why the game designers would make them both T6.

Well… here’s the issue with Warhammer – in every one of their games, they are endlessly devoted to the 6 sided die (d6). And I get why! Players can be reliably expected to be familiar with and own at least a handful of six sided dice. Only in the era of Critical Roll have we reached a point where any given board game store will reliably sell a set of larger polyhedral dice. Also, the odds on a d6 are really intuitive and simple to manipulate. If I need to roll a 4 or higher, I know I have a 50% chance of making that roll. Simple. Finally, six sided dice guarantee that any modifiers to your rolls are impactful. That 50% chance goes to a 2 in 3 chance if I need to roll a 3 or higher instead. This helps ensure choices in games create big satisfying jumps in success rate for players.

Tragically, this also means that you don’t have much in the way of nuance in your rolls. A single 6 sided die can have no higher a success rate than 5 in 6 if we assume a 1 will always fail and a 6 will always succeed (as Warhammer games broadly do). That’s fine if you want your game to be really swingy, but that’s not a great set of odds if you’re hoping to have somewhat consistent results. How do you make a beast like Ghaz up there survive a hail of gunfire if even the weakest weapons in the game have a 1 in 6 chance of injuring him?

Wathammer’s solution? Roll lots of dice, repeatedly. Instead of rolling a single 6 sided die one time, you’ll roll that same die multiple times, with a chance to fail and stop rolling each time. So when a unit of 20 Space Marines shoots at Ghaz, first you roll 20d6 to see if any of the attacks hit, removing any misses from the pool. Next, you see if those hits wound, requiring another roll (the one where Toughness plays its part), once again removing failed dice. Only then do you test to see if armor saves the target from injury. If any dice remain after that, the target takes damage equal to the number of dice, and that damage is removed from their hit point pool (called wounds in Warhammer, but it’s hitpoints in every way that matters).

That’s a lot of goddamn dice rolls, but it results in a much smoother results curve. While individually these dice are very random, the results of a Space Marine unit shooting at Ghaz with their standard weapons are fairly predictable.

So okay, what’s all this matter for then? Have I just conned you into reading about the world’s most repetitive dice rolling mechanic instead of discussing history? Of course I have, but also, I’m getting to the point. See, because you have to do all that work to smooth out the results, you can’t throw a spanner into the works like giving Ghaz a bunch more Toughness than that Space Marine. At T6, Gaz can feel fairly confident against (though not immune to) small arms fire, but still has to watch out for anti-tank weaponry. Raise that toughness any higher, and suddenly Ghaz is operating on a totally different level of durability, requiring much heavier weaponry to dispatch.

So why is this guy so annoyed that Ghaz’s toughness doesn’t match up to the scale of his model? Digging into the comments, we can see people arguing that it’s forgame balance, but clearly that is not the issue this poster is discussing. We also see several other commenters annoyed that Warhammer has moved away from “simulating a battle” and towards something more like a competitive sport. It’s a range of thoughts, but clearly the decision to set Ghaz’s Toughness to 6 is a gameplay one, right? They had to find the balance of where he would be compellingly tough, but also vulnerable to the types of attacks they wanted him to be vulnerable to.

Of course, that doesn’t engage with the original poster’s question at all, right? He knows that there can be gameplay concerns for a higher Toughness, but look at the fucking guy! He’s huge! He’s Ghazghkhull Mag Uruk Thraka! One of the most feared and powerful Orks in the galaxy! Shouldn’t he be tougher than a random space marine?

We do see someone, more helpfully, arguing that while Ghaz has more armor and is larger than the marine, he is wearing lower quality armor, and this therefore accounts for his Toughness being the same. But, hang on. Now we’re talking about armor, isn’t there a separate value that represents armor? The Armor Save! So what does armor have to do with Toughness? Well the poster argues that Toughness represents kind of an amalgam of armor and physical toughness, and that Wounds represent how much actual meat a target can lose before they die or are badly injured. It’s a logical, clearly laid out case for the reality of the Warhammer world: Toughness is both armor and meat, Armor is just armor, and Wounds is just meat. Easy!

Except it’s not at all. It’s a mess. And did you notice something weird earlier with our dice rolling? You might not have spotted it, but I’ll tell ya: When you roll to see if an attack wounds the target, you first check to see if the attack connects with the target. So far so good. THEN you roll to see if the attack is strong enough to wound the target through their toughness, THEN you see if the armor saves them from that wound. Do you see the problem? Logically, doesn’t that feel a bit backwards? If a laser blast is moving towards injury like a knife cutting an onion, then the first question should be does the knife hit the onion, then does the outermost skin of the onion cause the blade to slip off to the side, THEN does the blade dig deep enough to damage the onion. Armor goes outside skin even if, as the poster above claims, Toughness represents some amalgam concept of armor and meat, the pure armor save should happen first, right? Armor outside skin.

And yet, despite that logical contradiction, we have players arguing about why such a large model has the same Toughness as a much smaller one. We know the answer: it’s for game design reasons, but the in fiction reason matters to these folks. It matters incredibly. However, unlike examining the relative durability of an Abrahams tank in a World War 2 historical game, we don’t have real world data to go off of. Ghaz, as much as it pains me to say it, isn’t real; nor is anything much like him real. How tough should a massive, semi robotic fungus alien (the orks are fungi, don’t worry about it) be? What about the relative strength of a gun that shoots plasma? Swords made of alien chitin? We don’t know! We can’t delve into history to find the answer. We can’t, as the historical wargaming nerds of yesteryear did, pour over historical documents to discover the relative accuracy of Napoleonic war troops, or the durability of a Spitfire fighter plane, or the average speed of a camel laden with ammunition. As a result, our history books ARE rulebooks. Ghaz has been tougher before, so why isn’t he now?

This idea startled rattling my mind because of a new Killteam that came out. Killteam is a skirmish game set in the Warhammer 40k universe that, while using lots of the same terminology and general concepts as the larger game, is a completely different game with completely different needs. For example, the attack rolls of Killteam are completely different than those in larger Warhammer.

And yet…

Last year, Games Workshop released the Kasrkin Killteam. The Kasrkin are a legendary elite unit of human soldiers, trained and equipped by and with the finest the Imperium has to offer. To represent this, they have a currency called Elite Points which allows them to modify dice rolls in their favor. It’s incredibly flavorful, and works quite well on the tabletop. The complaint that I heard time and time again (and that I still hear now and again) is that they don’t hit on a 3 on a d6, but on a 4. This, as you might have guessed, is non standard for elite troops in Warhammer. Kasrkin and other elite human units generally hit on 3s. This is considered so standard that people found the very idea that Kasrkin would hit on 4s offensive, even when it became clear that this number works! It feels good in gameplay, and the Elite Points system makes the Kasrkin feel like the elite precision troops that they are. But that hit number represents something very very specific to Warhammer players, even in a system that handles attacking completely differently. As we saw above, despite the nonsensical nature of the process of injuring a target, despite the fact that Killteam is a completely different game to Warhammer 40k, despite the fact that Kasrkin don’t exist, and we can’t use real world stats to compare, players of these games have some hook into the reality of this world. Stats and rules are that hook.

Without a real history to work from, Warhammer players have been forced to create their own. Games cannot easily change themselves without rubbing against that history, without challenging not just ideas of balance, but the very fictional foundation these universes are built on. Games are always, always, a simulation of reality: a tiny window into the minds of the people that make them, and their understanding of the world. When I drop a ball, I can see how gravity affects it. When I want to know how accurate an average Napoleonic soldier was, I can pour over historical data and discover an approximation of that truth. All games are an abstraction. Pinhole visions into Truth. When you don’t have gravity, or statistics to use as the basis for your truth, what do you have to turn to but the fictional rules you’ve created?